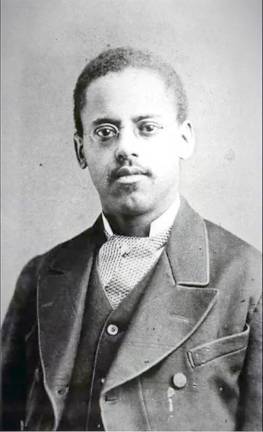

Although not a household name like Alexander Graham Bell or Thomas Alva Edison, Lewis Latimer contributed significantly to the inventions that made them famous and went on to build a very successful career of his own.

Born of escaped slaves in 1848, Latimer had to grow up fast when his father disappeared in 1857 after the Dred Scott Supreme Court decision, likely fearing a return to slavery. Nine-year-old Lewis had to find work to help support his mother and three siblings.

At 15, he lied about his age to join the U.S. Navy for the Union during the Civil War. After being honorably discharged in 1865, he eventually became an office boy with a patent law firm and taught himself mechanical drawing, earning promotions up to head draftsman.

In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell hired Latimer for a rush job: create the drawings for his application to the Patent Office for what we know as the telephone. Latimer worked long hours with Bell to complete the application; they submitted it just a few hours ahead of another application for a similar idea.

Thomas Edison’s chief rival, Hiram Maxim, hired Latimer as an assistant manager and draftsman at his U.S. Electric Lighting Company in 1880. Maxim wanted to improve on Edison’s incandescent light bulb, which could only last a few days. Latimer succeeded in modifying the filament to make light bulbs last much longer and be less expensive, which enabled widespread use of electric lighting on streets and in homes.

Latimer’s reputation in lighting expertise took him to Philadelphia, New York City, Boston and Montreal, leading planning teams and overseeing lighting installations in major buildings and streets. Maxim also sent him to London to set up a new division and supervise the production of Latimer’s own carbon filament invention. There he suffered the most discrimination in his career: English businessmen were not accustomed to – or particularly interested in – being directed by a Black man. But Lewis Latimer succeeded.

In 1884 he started working for Edison in his legal department, becoming immediately indispensible in finding patent infringements and defending Edison’s patents in court, as well as searching patents for new opportunities. He also translated data into French and German. Latimer was the only Black member of the “Edison Pioneers,” chartered in 1918 by 28 men who had worked closely with Edison in his early years.

Always thinking and observing, Latimer patented his own ideas that led to improvements in elevator safety and railroad car bathrooms, and invented an early type of air conditioning. At the time of his wife’s death in 1924, they had been married for 41 years and had two daughters. They were life-long active church members, and Latimer had stayed involved with Civil War Veterans’ groups and supported the civil rights activities of his era. He also taught mechanical drawing and English to immigrants, played the flute, and wrote plays and beautiful poetry.

Lewis Latimer shared an approach to innovating similar to Edison but with more humility: “We create our future, by well improving present opportunities: however few and small they are.” In 1968 he was honored by a Brooklyn, NY, public school being dedicated as P.S. 56 Lewis Latimer School. In 1995 the city of Bridgeport, Conn., erected a bronze statue of Latimer holding up a light bulb.

Learn about Latimer and Edison by reserving your private, free tour of “Thomas A. Edison: The Person, The Vision, and His Genius,” Sparta Historical Society’s special exhibit at the Van Kirk Homestead Museum continuing now through spring. Alternatively, time can be reserved to independently study the exhibit. Reserve by calling 973-726-0883: wait for menu options then press #2.

Sparta Historical Society