Big-box country

Business. Rural towns grapple with an ‘intense proliferation’ of warehouses that keep getting bigger. This is the first of a two-part series.

Ready or not, the mega-warehouses are coming to town.

The largest is a 3.2-million-square-foot, five-story “advanced e-commerce center” powered largely by robots and conveyors, proposed for the Town of Wawayanda in Orange County, N.Y. If it goes through, “Project Blue Bird” - one of 11 mega-warehouses on the table for Wawayanda alone - will usher in a new breed of logistics hub on a scale this region has never seen.

“I’m not saying that necessarily the town meant to do it this way, but it was a big secret. All of a sudden we find out at the last minute that a lot of these projects have been approved,” said Leslie Hanes, a retired teacher who helped found the grassroots group Save Wawayanda. “We’re talking about taking a semi-rural, suburban area and making it an industrial corridor.”

More than one in six Hudson Valley residents live within a half-mile of a mega-warehouse – defined as 200,000 square feet or larger – according to a recent report by the Environmental Defense Fund, a climate-focused nonprofit. In Northwest Jersey, one in fourteen people live within a half-mile of a mega-warehouse.

“Would I like other things besides warehouses? Of course,” said Wawayanda Supervisor Denise Quinn, whose family has lived in the town for five generations. But, she said, “for every person who’s against it, I have two people who come up to me who, you know, support it.” Already, warehouses have lowered her town’s tax levy to half what it is in neighboring Greenville, she said.

Some welcome warehouses for the jobs, tax ratables and local business they bring to delis and pizzerias. Others, alarmed by the prospect of air pollution, noise, traffic and paved-over farm fields, are organizing for a David versus Goliath showdown.

Orange County is ‘such a magnet’

In the age of next-day delivery, companies like Amazon “are desperate to come here,” said State Sen. James Skoufis. “Because we sit at the intersection of routes 17 and 84 and 87 and have significant cargo coming into and out of Stewart Airport, we’re close to the city, we’re close to freight rail lines.” Skoufis, who calls Orange County’s “intense proliferation of these distribution hubs” over the last five years “completely out of control,” is fighting a proposed 1.7-million-square-foot, five-warehouse complex in his hometown of Cornwall, where he is trying to arrange an alternate deal with the landowner to consider a lower-impact project instead.

The big box boom is cooling down nationwide from its pandemic height, and Orange County too has seen fewer buildings go vertical this year, said Maureen Hallahan, president of the Orange County Partnership, whose mission is to build the local economy by attracting and expanding businesses. Still, the county remains “such a magnet” thanks to “the ease to market and the wide open space,” said Hallahan. “We have a tremendous amount of land,” along with access to infrastructure. “You got gas and power, you can write your ticket,” she said.

Wawayanda’s mega-development boom comes as the industry-friendly town of Montgomery, 20 miles further east along I-84, nears its saturation point. Montgomery’s heavy build-out saw the county’s first three million-square-foot warehouses go up in the span of two years, beginning with an Amazon fulfillment center in 2021. The town is now home to about 20 warehouses of 100,000 square feet or more – built or approved to be built. Another pair of buildings totaling nearly a million square feet is in front of the Montgomery Town Planning Board, brought by Real Deal Management Group (RDM), a New Jersey-based industrial developer with mega-warehouses in the pipeline across Orange County.

State Assemblyman Brian Maher, who was supervisor of Montgomery when the million-square-footers went up, believes that warehouses have been, on the whole, an addition to his hometown as economic drivers. When they began to creep toward the village, though, it was a turning point, he said. “I don’t believe in putting them in the wrong places, which is what was happening in the Town of Montgomery. You’ve got to put them where the infrastructure exists, you’ve got to put them where the other ones exist,” he said.

An update in 2021 to the town’s comprehensive plan – protecting natural areas, wetlands and water quality; increasing buffer requirements; and maintaining the town’s character including scenic viewsheds – was a critical move that prevented three additional million-square-foot warehouses from coming in, said Maher.

Up next: Town of Wawayanda

Of the 11 new warehouses in front of the Town of Wawayanda, nine are the work of two developers: RDM and Scannell Properties, the first international developer to come into Orange County.

“I had no idea how huge it was,” said Hanes, after seeing plans for the pair of Scannell warehouses:Project Blue Bird and an adjacent 854,000-square-foot warehouse, which would both be built on a site that’s now an active gravel mine. “We’re talking two little cities,”she said.

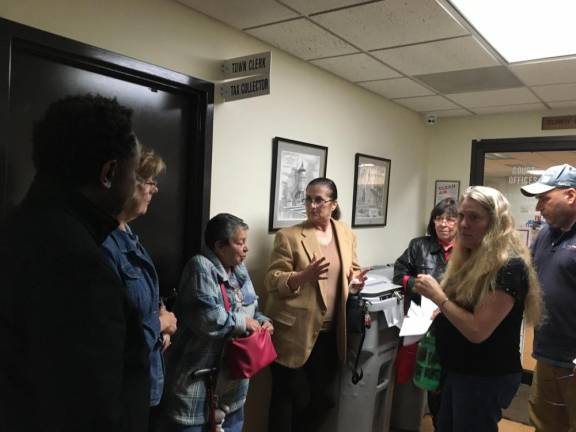

Matt Boone, development manager for Scannell, introduced Project Blue Bird at a crowded Wawayanda Town Planning Board meeting on Oct. 9. Members of Save Wawayanda clustered on one side, and on the other sat a group of men wearing light blue t-shirts, clearly hot off the press, that read “Support Project Blue Bird.”

Project Blue Bird started the application process under the name Slate Hill Commerce Center, but after Amazon pulled out, “we found another user,” said Boone. The plans he unveiled showed a warehouse that had stretched into something exponentially larger overall than the originally proposed million-square-foot fulfillment center. (Whether the new tenant could still be Amazon is hotly debated in town.)

Comprised of five stories of 600,000 square feet each, Project Blue Bird has a smaller footprint than the previous proposal, but at five stories high, three times the total floor space. Scannell has applied for a height variance for the building’s 94-foot roof.

Common across Asia and parts of Europe, multi-story warehouses are arriving in the U.S., made possible by nimble robotic systems that can sort, hoist and pick product from deep storage slots and sky-high racks.

Only 30 percent of the facility will be “occupiable” by people, said Boone, with the rest taken up by “mostly sortation, robotic and conveyors.” Without naming the warehouse’s future tenant, Boone gave a broad-brush overview of the expected workflow.

Tractor trailers come in full of bulk product from the “producer.” The product gets sorted and stored, then once it’s purchased, packaged and trucked to a last-mile facility which will deliver it to the customer’s home. Some 750 full-time workers on staggered 10-hour shifts – plus seasonal workers during busy seasons – will keep the warehouse operating 24/7.

The roof, said Boone, will be “solar-ready” – to be rigged with solar panels depending on whether Orange & Rockland can handle the load. The building will be all-electric, including heat, and rigged with “underground conduit so that in future, whenever EV trucks are a thing, we can easily then implement vehicle charging stations,”said Boone.

Its power demand will be so immense that the facility will require its own utility-scale substation.

The planning board seemed to be digesting the magnitude of the new project in real time.

“It seems like a significant amount more traffic that would be produced from this facility compared to the other one,” said Planning Board Chair John Razzano. “The numbers are just significantly more.”

“Do we have that much available?” another planning board member asked, of the 45,000 gallons a day of anticipated water demand.

A mounting resistance

“I think we’ll talk forever about this,” Razzano told Boone, along with the rest of the packed town hall. “A couple years ago, when we got the approvals, I’m not sure if it was an anomaly or what, but we had virtually no public comment on anything.”

“None of us knew,” muttered a woman in the audience.

“Since then, just recently, we’ve had three public hearings on a facility 10 percent this size,” said Razzano. “And we listened to over 10 hours of negative public comment and reams of paper associated with public concerns about traffic and noise and pollution and every other thing. So just fair warning on that, things have changed in a couple years.”

“I’m aware,” Boone replied quietly.

‘Which project are we talking about?’

“I have to say, we’re having a lot of trouble sorting this out,” said Hanes, of Save Wawayanda. “They came in with all these projects at once, and they had different names.” Real Deal Management’s proposed 235,000-square-foot warehouse, for instance, is known alternately as RDM#3 and Dew Point South. And Project Blue Bird is also known as Scannel #600 LLC, which started its application process as Slate Hill Commerce Center.

“Even Mr. Razzano,” the town planning board chairman, “I’ve heard him say a few times, now which project are we talking about?,” said Hanes.

It’s standard industry practice to use code names and to strictly guard the identity of a development’s future tenant. “That’s just the open market,” said Hallahan. “Companies don’t want their competition to know where they’re looking to expand, you know?” Even the Partnership sometimes goes into meetings with a site selector, she said, not knowing who the big boss is.

What kind of a community are we?

When Quinn grew up in Wawayanda, it was a farming community, but most of that land hasn’t been farmed in decades. “If you look at 211, when I was little, it was just a two-lane road. Now it’s a very busy road. And I wouldn’t want that to happen for us,” she said.

But the phenomenon of putting warehouses on former farmland is not a head-scratcher. “It’s because of how much everybody shops from home that now all of a sudden we need so many warehouses,” said Quinn. “You go to the mall and it’s hard to find what you’re looking for, and you go online, and it’s easy to find what you’re looking for.”

Quinn understands why some residents are against all the new development in town, and she has her own concerns about quality of life. But it’s thanks to the warehouses that Wawayanda’s taxes are lower than neighboring towns’, she said. “It’s very difficult to see our seniors who are struggling, who only live on Social Security, who are struggling to make ends meet, you know. And by having more ratables, it allows us to bring the tax rates down.”

Wawayanda’s year-long moratorium on new warehouses recently expired, and the town is working out a zoning change that will increase the setbacks between a warehouse and the property boundary, said Quinn.

“I know we have to have some growth. But it’s just ways of doing that without totally changing the character and creating a huge nuisance factor for everybody who lives here,” said Hanes, who lives in a 250-year-old house abutting a historic one-room schoolhouse.

Hanes would like to see the kind of development that enriches Wawayanda, population 7,400. Perhaps a ballfield where her grandson could play competitive baseball, or a transformation of the defunct railroad into a bike path.

Industry of this scale has no place in a rural town, says Malick, founder of Protect Orange County. “We’re not taking about a little auto mechanic, or garage, or restaurant,” she said. “It’s going to drive residents away, and then it’s going to destroy our wetlands, destroy endangered species habitat, which is then going to invite more industrialization because it’s already going to be brownfield sites.”

Western Orange County is touted statewide for its vineyards and breweries, bordering New York’s famous black dirt region. “They’ve got to pick,” said Malick. “Are we an agritourism destination? Or are we an industrial site?”

Wawayanda’s heavy industry will abut an affordable housing complex and border Middletown, whose population of 30,000 is heavily Hispanic, points out Malick.

The addition of over 1,000 trucks a day expected to service Wawayanda’s new warehouses – plus commuting warehouse workers – is a top community concern. Residents are worried about traffic, particularly during the morning rush to school and work; truck noise 24/7; and truck exhaust, which causes air pollution to spike around large warehouses.

Exposure to traffic-related air pollution not only exacerbates childhood asthma, but can induce the chronic condition, said Dr. Alan Schaffer, of Hamptonburgh, a pulmonologist who spoke at a Wawayanda Planning Board meeting in September. “You could have a child who would otherwise not have asthma be exposed to this air pollution and then develop asthma, and that’s just horrible,” he said. Truck exhaust also harms health in all sorts of less obvious ways, contributing to preterm birth and low birth weight, dementia, heart disease and stroke, according to the Environmental Defense Fund.

In Senate District 42, which covers nearly all Orange County, about 4,800 truck trips were being generated daily by the district’s 78 warehouses of 50,000 square feet or more, according to a January report by the Environmental Defense Fund.

More than a third of the mid-Hudson Region was designated a “disadvantaged community” last spring, a new classification by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation that takes into account asthma and heart attack hospital visits, air quality, unemployment rate, percentage of non-white residents and premature deaths. Montgomery and Wawayanda are in the middle of a contiguous belt of disadvantaged communities that runs the entirety of Orange County, east-west along the I-84 corridor and then up I-87, a pattern that echoes the distribution of warehouses.

Rushing to beat new regulations

Developers may be pushing warehouses applications to beat a regulation coming from New York State that will strengthen protection for wetlands in 2025. “I think they’re trying to grandfather all this stuff and get it in before any changes come,” said Hanes.

As of January, a million additional acres of wetlands will fall under state jurisdiction, which includes a 100-foot buffer around protected wetlands.

Documents obtained via the Freedom of Information Law show that the Orange County Partnership has been focused on the new wetlands mapping. The group hosted a Zoom presentation on the topic in September for a long list of who’s who in the county including developers, County Executive Steve Neuhaus, and town supervisors of Wawayanda, Goshen and Montgomery – the three towns contemplating major developments. Hallahan then sent a group email attaching a draft letter to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, which she suggested customizing with “specific and global concerns.” She called opposing the new wetland regulations a “critical group effort.”

A controversial mission

The Orange County Partnership has attracted criticism in Montgomery and beyond for its role in courting mega-development.

The Partnership brings in about $1 million a year, most of it from “investor fees,” according to its 990 filings, the most recent from 2022. Treetops Companies, the developer seeking to build the 1.7-million-square-foot warehouse complex in Cornwall, is among 50 major investors in the Orange County Partnership, according to the nonprofit’s website. So is CPV Valley LLC, the energy plant built in Wawayanda in 2018 in the wake of a bribery scheme.

Skoufis calls the Partnership a “legal racket” with no regard for taxpayers, the environment, “good-paying jobs,” or the values held by a vast majority of Orange County residents.

He is a vocal critic of the Partnership’s focus on helping companies like Amazon secure “enormous property tax breaks, which is just a blatant slap in the face of taxpayers, because at the end of the day, no one has to beg these companies to build warehouses in Orange County,” said Skoufis.

Hallihan is proud of her organization’s role over 38 years in transforming Orange County from the kind of a place where parents can work close enough to home to coach their kids’ soccer teams. The Partnership has helped attract businesses like Medline, LEGOLAND, Cardinal Health, Pratt & Whitney Aerospace, President Container, Pillar Power, McKesson, “and many other job creators filled with local people working and living in our communities,” resulting in thousands of local construction jobs and “millions of dollars in taxes to our school districts and our towns,” she said.

Compared to the landscape of Orange County 40 years ago, “we’ve grown in a very positive, very deliberate way,” she said. “And you’ll never hear the Orange County Partnership this viciously attack a senator,” she added.

“Economic development is not an easy industry, especially when we are competing with other states that have lower cost of doing business,” said Hallahan. “Despite criticism, I think it’s critical that we focus on reducing taxes and improving the business environment to keep New York competitive.”

Planning ahead

There’s not much a community can do once a developer comes knocking – not without risking an expensive lawsuit.

It’s happening right now in Sparta, NJ, where the developer of a proposed 660,000-square-foot warehouse sued the Sparta Planning Board in April for publicly opposing the warehouse on social media - and won.

“Sparta’s experience is a cautionary lesson,” said Sparta Mayor Neill Clark, an attorney himself. He urges officials in other towns “to be transparent and to carefully gauge the public’s support for large land use projects before such applications are filed.”

Being proactive is key. “The way to stop this is before it happens, before the application is submitted, and the way to do that is to have ironclad zoning, to have a smart comprehensive plan,” said Skoufis. “Municipalities’ hands aren’t completely tied, but they are in many ways tied once there’s an application in.”

Montgomery knows how dangerous it can be to make zoning changes in a hurry. The town lost a lawsuit in 2006 when a developer sued Montgomery for changing its zoning in an attempt to stop a multi-family housing development from coming in. After paying more than $700,000 in legal fees, the town had to revert back to the original zoning.

The town learned its lesson, explained Maher. As supervisor, he spearheaded an update to the town’s zoning restricting where mega-warehouses can locate, while still allowing them in the industrial corridor.

Still, “it was a little too late to do what we did,” he said. “I was elected when I was elected,” but had those changes happened five years earlier, they could have had a far greater impact, he said.

In a rare instance of successful community opposition, the Milford, Pa. Township Planning Commission last December unanimously rejected a 434,000-square-foot warehouse proposed for a prime piece of real estate between I-84 and Route 6. Locals mobilized under the “Water not Warehouse” banner, arguing that the warehouse – which would have been the largest in Pike County, Pa. - would risk polluting a drinking water aquifer. After the prospective land buyer pulled out, Milford turned its attention to changing the township’s zoning to protect the aquifer from future development.

Another route to preservation is for a landowner to sell their property’s permanent development rights. That’s what happened with a 150-acre horse farm being eyed for a mega-warehouse during Maher’s supervisor tenure. The Orange County Land Trust bought the development rights in 2022 for $10 million less than the developer was offering. “It was actually a beautiful story where you have these people that, you know, could have sold out,” said Maher. Instead, “we talked to them, we explained what the situation was and what our vision was, and they bought into it.”

Next in the “Big-box country” series: How life has changed in Montgomery. Contact the reporter at becca.tucker@strausnews.com if you work at a warehouse in town or have input.

“Would I like things besides warehouses? Of course. (But) for every person who’s against it, I have two people who come to me who support it.”

- Denise Quinn, Wawayanda supervisor